The attractions of the industrial analog market

In the $500 billion-plus semiconductor market, analog sits as an attractive niche. New entrants are not common in the space, margins and revenue growth can be attractive for the best quality companies, and product lifetimes can last for even multiple decades, giving resiliency and attractive cash-flows in the cyclical semiconductor industry.

Within analog, the industrial end-market can be particularly attractive due to extremely long product lifetimes. For example, for Analog Devices (ADI) — a player focused on this end-market — 50% of revenues stem from products over 10 years old:

This means that sunk capex can generate cash-flows for extremely long periods of time, as semicap equipment doesn’t tend to break down. ASML for example estimates that practically every tool they ever sold is still in use.

These long product lifetimes make it also especially hard for new entrants to break in into these markets, as you can only very gradually build up revenues at the rate of sockets opening up for new products.

Additionally, there is much less focus on analog semis in academia, so you have to learn how to bake these semis on the job, which I’m being told is somewhat of an art. This again makes it harder for new competitors to start competing, as opposed to for example in digital semi design, where it is much more straightforward to start a business due to the comparatively higher availability of engineers combined with a capital light business model.

As investors, we also get no customer concentration risk as we have with TSMC for example where Apple, Nvidia and Qualcomm are very significant customers. On the contrary, the large players in this field typically sell around 100k different SKUs to a similar amount of customers.

Pricing power is actually decent for the quality companies in these fields, as due to the long product lifes, some price increases can be implemented over time. The typical analog semiconductor sells for less than $0.5 per piece, so cost reductions are not an area of focus for customers here, especially for manufacturers of highly-priced industrial equipment or automobiles. The other source of price increases is innovation, as more advanced products sell at higher ASPs when they are introduced.

ADI’s CEO, Vincent Roche, discussed their pricing strategy at the UBS conference:

“So typically, when we get a design established, in the industrial business, those sockets will last for 17 years on average. And then consumer is somewhere between 3 and 5 years. But when we get the socket, the pricing is very steady over the life of the product. So these are very sticky products and there’s many places in which we play, so there’s a tremendous diversification.

But the price increases that we put on our customers during ‘21 and ‘22, they will stick largely. If there are price decreases in the portfolio over time, that has been agreed upfront and that tends to be based upon a volume to price relationship. So if the volume occurs that we’ve agreed upfront, there’s a certain price reduction associated with that. But there are parts of the portfolio as well, where we actually increase prices over time, typically older vintages that we maintain for 20 to 40 years.

Over the last couple of years, we got half of our growth from pricing, basically repricing our products to the level of inflation that incurred in our cost of goods. But generally speaking, we’re adding more ASP value to our portfolio every year. We’re doing that through innovation. For example, our 5G transceiver technologies compared to 4G. We also are able to add some software value to the products, that gives us a little more ASP again.

So new products in particular, we’re increasing the ASPs. 7 or 8 years ago, every year we would face probably a 5% price concession compared to the prior year’s revenue, those days are finished. So that’s very stable now.”

The other big player in this field is Texas Instruments (TI). TI’s new CEO, Haviv Ilan, a 24-year veteran at the company, discussing their views on pricing and where to play in the market at the Bernstein conference:

“We’ve learned that the higher the ASP, and the higher the volume per socket times ASP, the more competitive the market is. It’s hard to maintain margins. When you serve a $0.25 to $0.30 a socket, price is not the biggest thing. It’s performance, power and feature of the part. We make good margin on this.”

The quality of a semiconductor manufacturer is often measured by the strength of the gross margins, the difference between what you sell the semiconductor for and how much it cost to manufacture it. Both ADI and TI are among the best in class on this measure, which has been translating into attractive FCF generation as we’ll see later.

These high margins are no surprise as both ADI and TI have been orienting their business towards the more attractive parts of the market, both via M&A as well as internal R&D.

Analog semis are used to measure the physical world, such as temperature, pressure, and audio. So unlike digital chips, where transistors can take on two states i.e. 1 and 0, analog transistors take on a continuous range of values to reflect these real world measurements.

An analog semiconductor consists of multiple transistors, connected to achieve the desired functionality. A variety of analog semis are connected in a typical system, converting these measurements to provide signals to a digital computing unit, which uses this information to perform calculations and send instructions to the output systems.

Analog semiconductors can perform a wide variety of tasks, such as amplification, filtering, and signal conversion. And they are also used to manage power in electronic equipment, i.e. PMICs or power management integrated circuits.

ADI illustrates the variety of tasks their products can perform in a typical workflow:

An image of a MaxLinear PMIC on a Raspberry Pi:

Looking at end-market demand, both the number of products making use of semiconductors has grown, as well as the semiconductor content per product. Semiconductors are taking on ever more tasks, from heating the seat in your car, to the same seat massaging your back, to providing you with an operating system to control your car and play a video game.

As such, the number of semiconductors being shipped annually has been on an attractive, upward-sloping trendline (chart below). And although the semiconductor industry has been going through one of the most severe downturns in its history over the last few years, TSMC’s and ASML’s commentary last month indicated that we are on the cusp of new bull cycle.

To illustrate this, ADI shows how its semiconductor content in robotic arms is increasing:

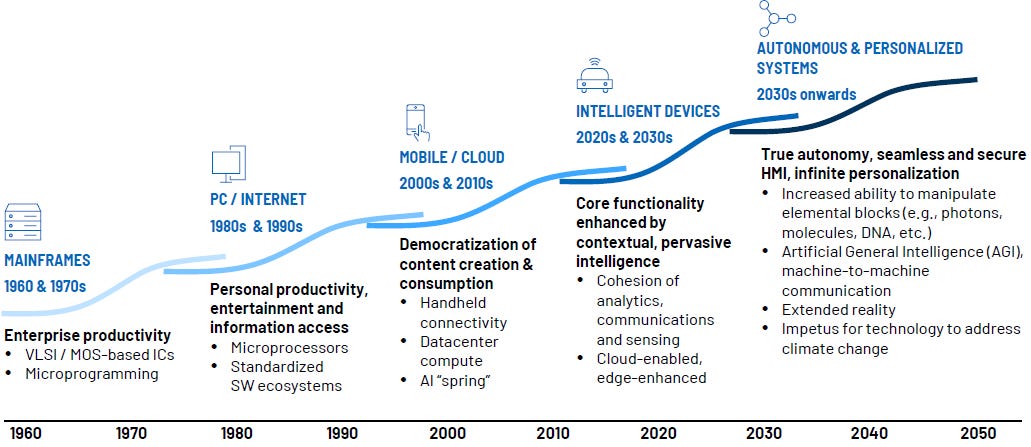

Most semiconductor firms have been providing similar charts for automobiles, and it won’t stop there. ADI illustrates how every decade, the demand for computing power has been increasing:

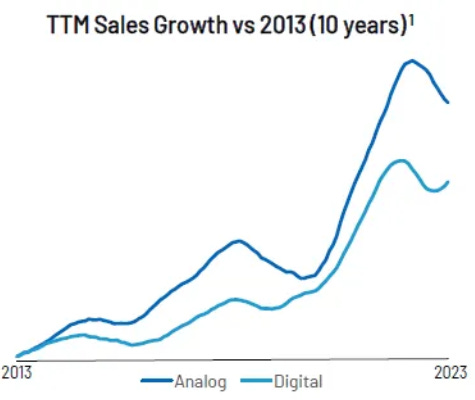

And according to the data from ADI, analog has even outperformed digital in terms of revenue growth:

So despite the low ASPs and somewhat ancient technology for semiconductors — as analog semis are manufactured on process nodes of around 90 to 300nm — analog firms can actually hold several attractions. Especially for investors looking for cash-generative and compounder-type stocks, as both ADI and TI are committed to return all free cash flow to shareholders, in the form of both dividends and stock buybacks.

For premium subscribers, we’ll do a deep dive on:

Texas Instruments and its fab strategy

Analog Devices and its counter strategy

How China is building up mature semi capacity and is aiming to disrupt the US analog semi industry

A financial analysis and thoughts on valuation for both names