AI Compute in Space Economics & A Deep Tech Disruptor

Planet Labs & Our Next Two Investments

AI Compute in Space Economics & Planet Labs

Planet Labs is a vertically integrated leader in Earth intelligence. Basically what this means is that the company builds satellites, gets them up into orbit via SpaceX, and then does a daily scan of Earth with its satellites to get insights into what is going on. Key customers are the US government and other allied governments around the world as thanks to AI, Planet Labs can detect all military infrastructure being built by adversaries.

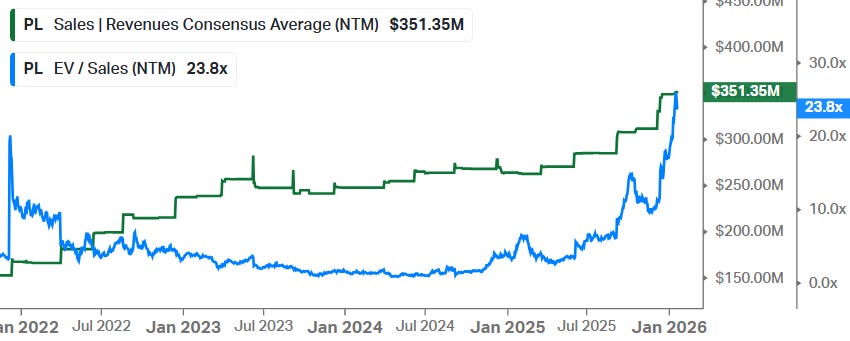

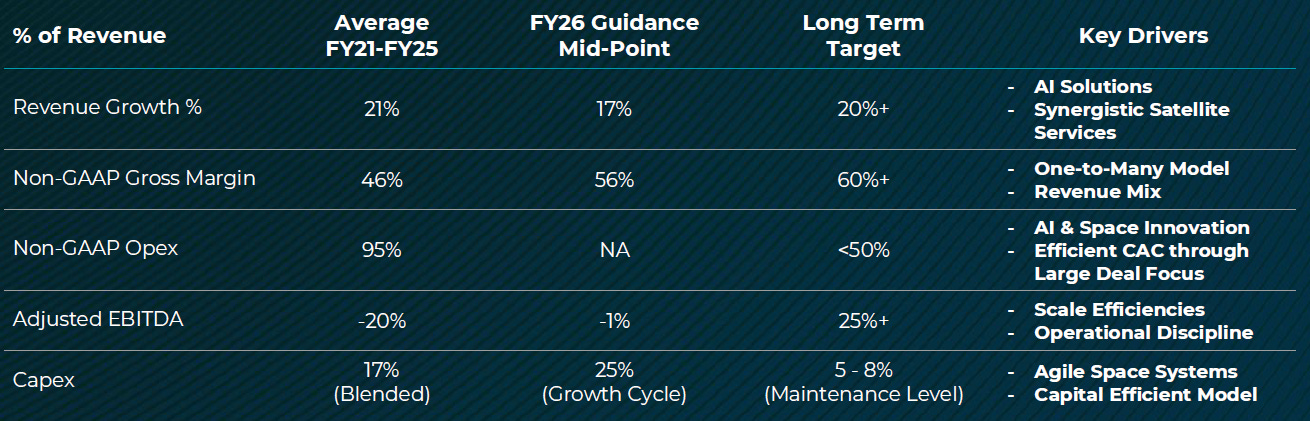

We like this company as barriers to compete are fairly high. You need to get a satellite network up into space, develop the systems to manage these satellites and analyze all imagery, and then create a portal so that customers can use it for insights. So, it’s a bit like an AWS or Bloomberg terminal for space-based data. This is a business with recurring revenues and pricing power. Gross margins are starting to get attractive at around 60% while the business has also turned FCF positive, and with a net cash position on the balance sheet. As valuation last year looked reasonable for the opportunity set, this is an investment idea we reviewed at the time and took a position in.

However, one of the reasons that we’re currently more cautious than the market—following a very strong share price rally over the last months—is that growth in commercial is actually down. So, growth is mainly coming from military intelligence for government customers. From the last call:

“Shifting finally to the commercial sector, where revenue was moderately down both year-over-year and quarter-over-quarter. While this trend is expected given our increased focus on large government customers, we remain confident in the commercial sector as a significant market opportunity for Planet, especially as we continue to advance our solution capabilities. We believe that AI-enabled solutions we’re developing for our government customers will enable us to deliver insights that can serve applications across a broad range of industries and use cases from supply chain, security, and optimization, to insurance, finance, energy and agriculture; where we have had a number of marquee customers today. We expect these solutions will help unlock growth in the commercial sector, bridging the gap from data to insights for those customers.

To share a recent commercial highlight, we signed a new operational contract with AXA, one of the world’s leading insurance groups following a successful proof of concept. AXA will integrate data from Planet Basemaps, our medium resolution monitoring satellite and high-resolution tasking fleets, to enhance claim processing efficiency and accuracy for property management. We’ve also signed a strategic marketplace agreement, which will add Planet’s products to AXA’s DCP platform, making them commercially available to AXA’s vast client network of insurance partners. This partnership marks a major step forward in proactive data-led resilience in the face of complex disaster and crisis management needs.”

We don’t disagree that Commercial can be a big opportunity long term, but the current valuation warrants strong execution. Currently, we see that traction is fairly limited and that revenues are actually down. The big positive though is that incremental margins on contracts such as the one with AXA are 90%. As all necessary costs have already been made, the margins on new business are huge.

What really catalyzed the shares to move higher was the following announcement on the recent call:

“Secondly, we recently announced a funded R&D initiative with Google called Project Suncatcher. Suncatcher aims to enable scaled AI computing in space by putting Google’s tensor processing units or TPUs on purpose-designed satellites where they can leverage the energy of the sun and shed excess heat into the natural coolness of space. This is a competitive win for Planet and our strong track record of building, launching and operating over 600 satellites to date. Suncatcher aligns well with our technology development roadmap for Owl, leveraging the same satellite bus and is therefore highly synergistic. As previously announced, we’re planning to deploy two prototype satellites in early 2027. We’re excited to be working with our long-term partner, Google, to develop this promising new technology.”

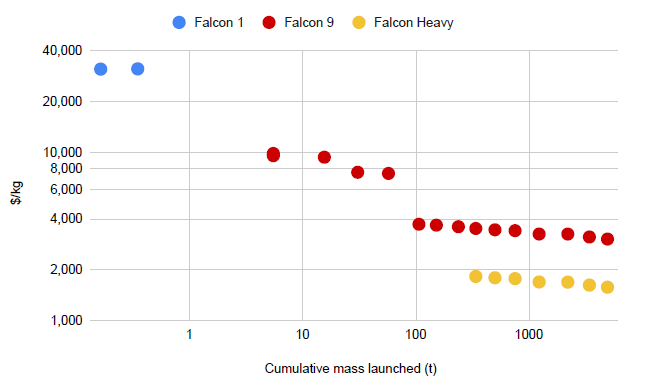

From the Google paper below—it looks like TPUs can handle the radiation in low Earth orbit (LEO) and that with the introduction of SpaceX’s Starship, launch costs will fall sufficiently far to make this economical:

“Trillium TPUs are radiation tested. They survive a total ionizing dose equivalent to a 5 year mission life without permanent failures, and are characterized for bit-flip errors. Launch costs are a critical part of overall system cost; a learning curve analysis suggests launch to low-Earth orbit (LEO) may reach ≲$200/kg by the mid-2030s.

SpaceX launch pricing data and mass launched from Falcon 1 to Falcon Heavy yields a ∼20% learning rate, meaning the price per kg falls by ∼20% for every doubling of cumulative mass launched (over all vehicle classes). If the learning rate is sustained—which would require ∼180 Starship launches/year—launch prices could fall to <$200/kg by ∼2035. While this would be a substantial achievement for SpaceX (particularly given the technological discontinuity inherent in switching to Starship), it is still far below stated launch targets for Starship. Even if this launch rate is reduced by ∼ 70%, prices could drop to $300/kg in the same timeframe, which would still have a substantial impact on feasibility of largescale constellations. Further, there is precedent for a sustained ∼20% learning rate over multiple decades in other advanced industries leveraging mass-production (notably, solar panels). Given the long lead times required to reach scale for this type of ambitious project, it’s strategically beneficial to commence work on early milestones in anticipation of projected price declines.

Alternatively, our analysis of Starship 4 public specifications and data suggests that SpaceX launch costs to LEO may drop to ≲ $60/kg (10× component reuse); if SpaceX’s 100× component reuse target were achieved, costs could reach ≲ $15/kg. Assuming 10× reuse and even the highest estimates of current SpaceX margins (up to 75%), launch price to customers would drop to <$250/kg (although margins are currently supported by SpaceX’s near-monopoly and hence likely to decrease with the anticipated entry of competitors such as Blue Origin). Realizing these projected launch costs is of course dependent on SpaceX and other vendors achieving high rates of reuse with large, cost-effective launch vehicles such as Starship.”

If SpaceX hits the conservative end of their Starship targets, we already get to $200 per kg. Assuming a future single Starship launch cost of $20 million—covering fuel, pad maintenance, and amortized hardware—and with a payload of 100 tons (100,000 kg), we get to $200 per kg. Both these numbers are the most conservative estimates from SpaceX for Starship. Elon has been mentioning that $20 per kg is the actual target.

Long term—we’re talking 2030s here—this could become an attractive business for Planet Labs. Assuming the company puts 3,000 AI satellites into space on an annual basis at $5 million in contract value per satellite, we get to a $15 billion annual revenue opportunity. Part of this revenue opportunity is that Planet would charge a maintenance fee for the entire Google satellite fleet in operation—managing the positioning of the satellites, monitoring the fleet, software updates, end of life management etc.—and these would come in on an annual basis post the launch, so part of the $15 billion annual revenue opportunity isn’t immediate. However, these would be extremely high margin revenues. The reason is that Planet has already built out the command and control center to manage its satellite fleet, and so additional satellites can now be added at little marginal cost. As these maintenance revenues would be recurring, they would attract a high multiple from investors.

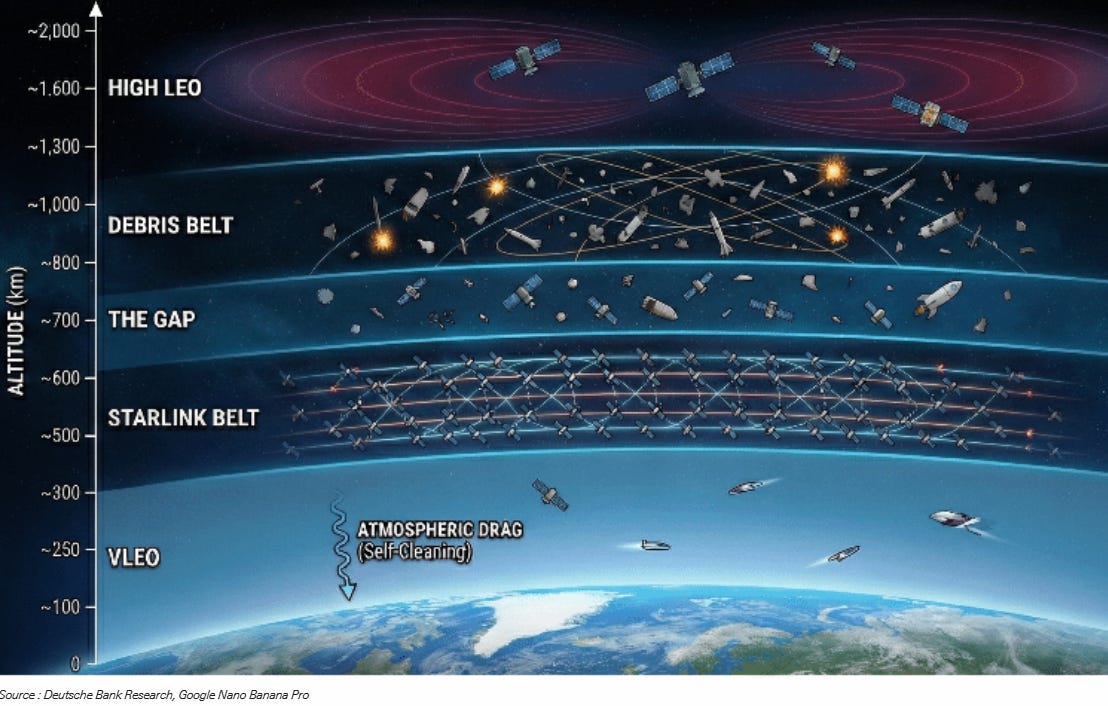

Why not more satellites for Planet? While AI accelerators are able to withstand radiation in low earth orbit, if we move them higher, they will get fried. So room in space is limited actually, it’s not like we can build unlimited data centers in orbit around earth. At the same time, there is a collision risk. So, you don’t want to pack too many satellites close to each other. One collision could create a cloud of debris that triggers a chain reaction called Kessler Syndrome, which could turn a specific altitude into a no-fly zone for centuries. Remember, fragments travel at 17,000+ mph and so they can punch through a satellite like a bullet.

The reason why this remains speculative is that we’re very early in this concept—tests will be done by 2027 and then maybe in the early 2030s SpaceX’s launch costs will have fallen sufficiently far to make this whole idea economical. If SpaceX’s progress is slower, this is a story that’s really a long time away, e.g. 2035 or beyond.

Some of the necessary innovations SpaceX has to make include firstly the catch. I.e. SpaceX must perfect to catch Starship with the tower arms structure called ‘Mechazilla’. Currently, they’re only catching the booster. Until Starship is reusable, you are throwing away the Raptor engines and a massive steel structure every flight, which is too costly. Secondly, the heat shield has to work. This is an extreme materials engineering problem. You need Starship to land and fly again within 24-48 hours, so without humans inspecting and replacing the heat tiles manually. Thirdly, volumes. SpaceX needs to be flying Starship 100+ times a year to amortize the costs of the launch pads and ground support.

So, while exciting, the partnership with Google and this bringing in sizeable revenues for Planet Labs by the early 2030s still looks somewhat of a moonshot. Timelines of 2035 and beyond are probable, which is really far out. Given a high potential value into a distant future, we suspect this is a share price which will be fairly volatile in the coming years, with sell offs and rallies. Although we do think that due to Planet Labs’ strong position in space infrastructure and its positive free cash flow, a high current multiple is justified. New investors looking to get in could wait for a pullback to exploit volatility.

Deutsche Bank has done some further modeling on the economics of data centers in space:

“After further refining our assumptions, we estimate the near-term cost of deploying a 1 GW space data center is at least 7x higher than terrestrial. This gap can narrow to 4x later in the decade and then eventually reach close parity in the 2030s. This reduction is primarily driven by decreasing launch costs and further optimization of satellite design and power efficiency, which leads to a lower amount of mass required for orbital deployment. We assume the current industry price of a launch to low-Earth orbit (LEO) is ~$70m or $4,000/kg. Over time, we assume the cost can decline materially to as low as $10m or below $70/kg with full rocket reuse and operational scale. We estimate the cost of a data center satellite to be $2.1m in the relative near-term or >$40k per kW.

For background, a satellite is typically made up of two main parts: bus and payload. The bus is the main structural framework and support systems of the satellite. It acts as the “vehicle” that enables the satellite to operate in space, maintain its orbit, and survive the harsh environment of vacuum, radiation, and extreme temperatures. Key components include the physical frame, solar panels, thermal management system, propulsion, and optical terminals. The payload is the specialized equipment or instruments that carry out the satellite’s primary mission. For a data center satellite (we refer to as a DCS), the payload is the GPU or TPU.

Why put these in space?

Energy – at the right orbit such as in dawn-dusk SSO (sun-synchronous orbit), solar panels can harness the sun’s free power 24/7 and importantly, garner 40% higher intensity than on the Earth’s surface due to a lack of an atmosphere filtering/scattering sunlight. As such, operators can generate up to 6-8x more energy in orbit (leveraging continuous availability + greater irradiance) and avoid dealing with expensive/complex power grids terrestrially and also eliminate battery backups.

Cooling – represents a large burden, accounting for an estimated 40% of energy consumption, having to use large amounts of water/piping. In fact, Nvidia’s Jensen Huang recently commented for a 2-ton GPU rack, 1.95 ton is cooling mass. In space, cooling will require attaching a passive radiator on the dark side of the satellite (i.e., part not facing the sun) which can dump waste into the vacuum of space.

Latency - optical laser links traveling through vacuum are faster than fiber optic cables on the ground, potentially by >40%. This is due to refractive index of glass and indirect path of travel for cables. In relation, satellites are increasingly generating data in space (e.g., imagery, weather data, climate monitoring). Currently, the data is downlinked to Earth for processing, which is slow and bandwidth-heavy. By having the data centers close to the satellites (“edge compute”), the processing can happen much faster in orbit with only the results/insights being sent back down.

From a TAM perspective, we think DCSs represent an entirely incremental opportunity for both launch and satellite manufacturing companies. The hyperscalers are very well capitalized and can easily fund future deployments if desired which was a concern for some previously proposed LEO mega broadband constellations (e.g. Rivada). Initially, we expect deployments to be small in order to prove out the engineering and economics, beginning in 2027-28. Should these be successful, we expect constellations to reach hundreds and then thousands of satellites in the 2030s.”

Deutsche has a lower cost per satellite than we modeled above, but we included in our calculation the gross margin Planet Labs will make plus the value of the servicing contract to manage the satellite in space. So, Deutsche’s number is basically a manufacturing cost. Therefore, $5 million in revenue opportunity per satellite seems reasonable to us. The big question mark will be volumes in the 2030-2035 period.

There is actually upside to this number as Deutsche notes that the cost per satellite will increase due to rising power requirements:

“Current satellites generate up to ~30kW of power (e.g. ViaSat-3) and we suspect this may need to increase significantly over time to >100kW. With much more power to run GPUs or TPUs, the satellite will need to utilize larger or more radiators and/or develop more efficient ways to transfer the heat from the chips to the radiator.”

While other costs in satellite manufacturing will decline due to economies of scale, the overall cost of the satellite will continue to increase due to increasing power requirements.

Overall, whereas we were initially inclined to take profits in Planet, after doing this writeup and properly reading through the Google paper and Deutsche’s modeling, we’ve decided to maintain our position here. Planet Labs is a rare pure play on the long term growth in space and that is actually making money with its positive FCF. Other space-related companies are typically burning loads of cash, with the exception of SpaceX. Planet Labs’ valuable Earth intelligence platform provides an attractive growth asset, while its capabilities in satellite manufacturing and management provide valuable long term optionality.

Optically, 24x forward sales for 20-30% annual top line growth in the coming years looks expensive. However, we think there will be more opportunities down the line—e.g. the Google deal being one of them—bringing in substantial upside in the long term. Typically, these types of well positioned companies in innovative industries find new revenue streams over time as openings emerge. Examples include SpaceX with Starlink, Amazon with AWS, Apple’s App Store, Nvidia with data center GPUs, Broadcom in ASICs etc. The recent Planet Labs-Google deal is just the latest example of well positioned tech companies finding new revenue streams which the market wasn’t even considering.

Also Deutsche hints at further opportunities down the line in space:

“Looking farther beyond, we think deploying large amounts of compute into orbit is important to cultivating efforts on the Moon and eventually Mars. DCSs orbiting the Moon can enable edge processing for AI autonomy, enabling real-time decision-making in habitats during communication delays. For instance, they might handle data from rovers or life support systems locally, fostering self-sufficiency for a permanent Moon base settlement.

Beyond that, Musk pointed to building satellite factories on the Moon (presumably leveraging Tesla Optimus humanoids) and then using a electromagnetic railgun (also referred to as a “Mass Driver”) to send satellites to lunar escape velocity without the need for rockets. This is because the Moon has just one-sixth the gravity of Earth and no atmosphere (no drag), thereby, requiring less effort to deploy satellites from the Moon. Musk believes this will ultimately allow for scaling up to >100 TW of AI.”

Planet Labs’ financial model from the investor day a few months ago is below, this is the model from before the Google deal and thus the optionality of AI data centers in space in the 2030s:

Next, we’ll discuss a name which is now in a similar position as Planet Labs was last year, i.e. an under-covered stock and with likely an even larger opportunity set. Revenue growth is already exploding, gross margins are top notch, and the company is already generating attractive GAAP operating margins. A rarity for a hypergrowth tech name. Its excellent financial metrics reflect the company’s strong positioning with a disruptive tech.

Given these characteristics, we see valuation as attractive here. It’s far cheaper than Planet Labs. The stock is also uncorrelated to the AI semis cycle and the current panic surrounding software stocks. So, it’s a nice way to diversify a tech portfolio with a more unique name and which should be looking at a long runway of growth in a massive TAM.

As a bonus, we’ll review one more name at the end where we’re currently doubling our position in. Again, this is a name that few investors will be aware of and with similarly a large long term opportunity.